Make a donation to the museum

Rescue & Recovery at 20: Philip Rizzo, DOC

Rescue & Recovery at 20: Philip Rizzo, DOC

- May 5, 2022

Philip Rizzo's NYC Department of Corrections ESU shirt and respirator

May 30 marks the 20th anniversary of the official end of the rescue and recovery efforts at Ground Zero. That day, we'll honor the courage and sacrifice of those involved and affected — in the days, weeks, and years that followed — with a special ceremony. Leading up to that milestone commemoration, we'll be highlighting the stories of rescue, recovery, and relief workers — many of whom now face 9/11-related illnesses — to recognize their tireless efforts, sacrifice, and spirit.

To acknowledge National Correctional Officers Week, we begin with a Q&A featuring the Department of Correction's Philip Rizzo, derived from our oral history collection.

Where were you on 9/11?

On September 11th, I was at Riker’s Island. I was a training captain for the Emergency Services Unit. One of our instructors came into my office and told me something happened. From Riker’s Island, we could see the smoke coming out of one of the towers. At the time, they were thinking there would be a major problem if something additional happened on Riker’s Island. With over 20,000 people on the island, they established a command post. The first thing we did was ensure all inmates were locked in their cells. Nobody was allowed out unless they had a medical problem.

Corrections Emergency Services had a hundred full time people and a hundred support people. All two hundred were told to come in and report to Ground Zero, even if they were off duty. After securing Riker’s Island, we were sent down to Stuyvesant High School, the command post for the NYPD. We previously trained with NYPD officers, so we had a bond with them, and they knew we were capable. We didn’t have specialized gear at the time, just our uniforms. By the time we got there, both towers had fallen.

Everything was white and covered in dust. I remember telling my partner, “We might be marching these guys to their deaths.” He said, “We all have to go sometime.”

It was an eerie feeling I had. The piles of debris blocking whole streets were hot, they were smoking from the fires. The place was so hot, you could barely get on the pile. We went to search the outskirts of the pile. We were outmatched, but we were going to stay there. We matched each officer up with a partner and started searching for people.

What role did you play in the rescue, recovery, and relief efforts?

The first night, we called it quits around 11 or 12 and slept on cots at Stuyvesant High School. The next day, we went down and did the same thing. I don’t remember when we started getting masks and equipment to search. We just had buckets, trying to clear the area to find people. We didn’t find anybody.

For the first six or seven days, we would work 12-hour tours, go home, sleep, and go back the next day. Some of the days there, all I remember is the smoke and smell of the remains. At some point, we started to find wallets, things like that.

For months, we kept our same routine. I would go to work at about 5 am. I would send officers to Staten Island at Fresh Kills Landfill. Then the Ground Zero crew would come in at 6 am, and I would send them out. Correction Department left Ground Zero around February.

Can you describe the bond between yourself and other recovery workers? How has this community impacted you?

I became a supervisor there so I had to have a different approach when we moved from rescue to recovery. It surprised me that we didn’t find people alive those first few days. I thought people would’ve got out of there. I had a lot of hope for the first five or six days, maybe longer than I should’ve had it. Then I had a conversation with a police sergeant. He said, “I’ve been watching you, you’re a good officer, but you’re not an officer anymore. We’re not going to find anyone anymore. You have to watch out for your guys.” The mentality of a first responder is to help, so it’s not easy to tell guys you’re not going to find anyone. That’s when I started to have a new phase about how I supervised them.

What does May 30th mean to you?

The place was going 24/7 and we cleaned it up. Today, when I walk around out there, it’s remarkable. It’s a lot of strength, a lot of people that did that. A lot of us feel very accomplished of what we did down there. After 9/11, there was nothing I felt I couldn’t get through.

Do you have any health issues connected to your time at Ground Zero?

I told my guys not to eat anything near the site. I told them to wash their hands before eating. If they had their water bottle, they shouldn’t put it back in their pocket, it should go in the garbage. The whole area was contaminated, and we were covered in dust. It was impossible to not be conscious of the dust, smoke, and heat. You knew everything in that building was burning. I knew from the start that it was a toxic area. At the time, I was being cautious. I couldn’t foresee that people would get sick, but I was cautious.

We started hearing people were getting sick much later. In 2005, I started to lose my voice a lot. I would be drinking water, but my voice was getting hoarser and hoarser. That’s when they found polyps in my vocal cords. They removed them, but that’s where everything started. That was before the Zadroga legislation was passed. Then I started having mild things, like shortness of breath.

For the generation who is growing up with no memory of September 11, why is it important to share your story and the stories of others with them?

There are a lot of 9/11 stories that people don’t know. A lot of people don’t know correction officers were there. It’s good that we’re [telling these stories] so someone in the future can learn more.

Anything else you’d like to add?

One of the eerie things I remember to this day was the beeping of the Scott Air-Paks in the rubble. The beeping meant that the person with that pack was not moving and needed help. We were searching, crawling through debris, but we had no equipment. Some of us had gloves, some of us didn’t. We were just trying to get through to them.

Compiled by Caitlyn Best, Government and Community Affairs Coordinator

Previous Post

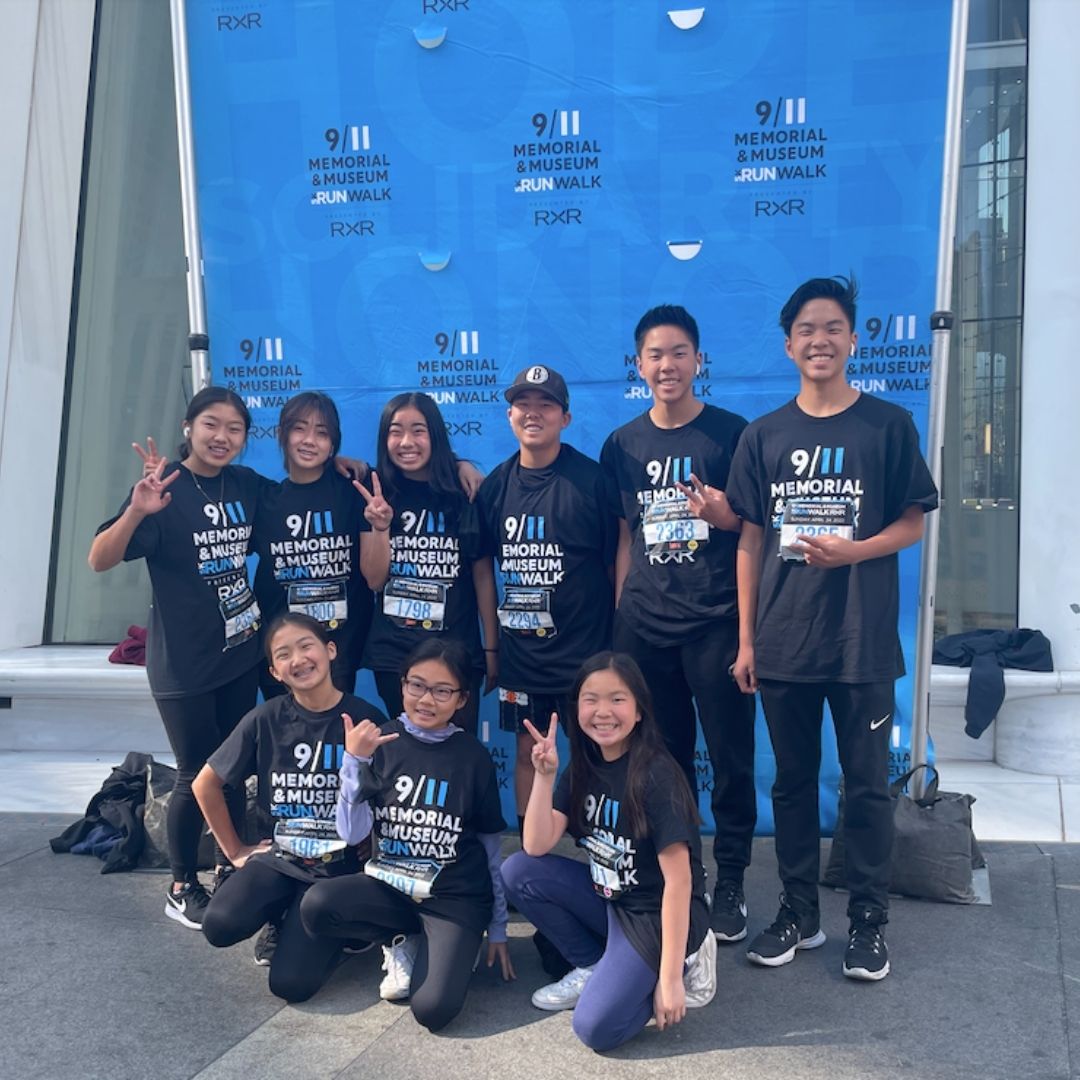

The 2022 5K in Photos

Thank you to everyone who ran, walked, fundraised, and volunteered at our 2022 5K. This year's event was a huge success and a wonderful show of community — your efforts help ensure the Memorial & Museum remains a sacred place of remembrance, reflection, and learning.

Next Post

Teacher Appreciation Week: Ada Dolch

Ada Dolch was a New York City educator who helped get her students and fellow staff to safety on the morning of September 11. She lost her sister, Wendy, in the attacks. This Teacher Appreciation Week, we are proud to share Dolch's story.